The mystery of the relationship between J. Edgar Hoover and his deputy Clyde Tolson has been solved — at least in the movies.

Clint Eastwood’s “J. Edgar,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio, portrays the former FBI director as a closeted homosexual who has a crush on Tolson but resists his overtures.

Given the fact that Hoover reigned as director for 48 years and was more powerful than presidents, “J. Edgar” should have been an epic movie. Good Hoover established the FBI as a technically advanced law enforcement agency. Admired throughout the world, the bureau has kept us safe since 9/11.

But Bad Hoover engaged in massive abuses that trampled on Americans’ rights and kept him in power. As Buck Revell, the bureau’s former associate deputy director over investigations, has told me, Hoover would be indicted today for using government funds for personal gain.

|

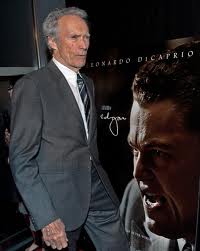

| Clint Eastwood beside the film's poster (AP photo) |

In remarks before the screening of the movie at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., Eastwood, a supporter of law enforcement, established his interest in portraying the truth and his fascination with Hoover.

By fairly dramatizing Hoover’s life and his importance in creating the FBI, Eastwood achieved that with the ambitious effort that opens Friday.

In a gripping segment, Eastwood focuses on the kidnapping of the 20-month-old son of Charles Lindbergh Jr. on March 1, 1932.

Lindbergh was an adored hero who had made the first solo non-stop transatlantic flight in his monoplane The Spirit of St. Louis. Any police force that could return the Lindbergh child to his parents would gain tremendous recognition.

State and local police had no interest in obtaining the bureau’s help. Nor would they share any evidence with what they called the “federal glory hunters.” For weeks, the bureau was denied facsimiles of the ransom note.

Undeterred, bureau agents investigated every lead, no matter how bizarre. More than two years after the Lindbergh kidnapping, on Sept. 15, 1934, a gas station attendant in upper Manhattan became suspicious when a customer paid for five gallons of gasoline with a $10 gold certificate.

All gold certificates were to have been turned in to banks by May 1, 1933, when the United States went off the gold standard. On the back of the bill, the attendant noted the customer’s vehicle license number — 4U-13-41 NY.

Three days later, when the gas station attendant turned in the note at the Corn Exchange Bank and Trust Company, the teller identified it as one of the marked bills paid as ransom in the Lindbergh case. The bureau had distributed notices to banks and other businesses asking them to be on the lookout for gold certificates. The notices listed the serial numbers of the bills used to pay the ransom.

The alert teller called the bureau’s New York Field Office. Checking back with the gas station attendant, bureau agents verified that the number written on the bill was the license number of the customer’s car, a dark blue Dodge sedan. It was registered to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, an unemployed carpenter living in the Bronx.

After his arrest, an expert linked the homemade ladder found at the crime scene to materials and tools in Hauptmann’s home. The need to analyze the ladder led Hoover to establish the FBI Laboratory on July 7, 1932.

A jury convicted Hauptmann on Feb. 13, 1935 in state court. On April 3, 1936, Hauptmann was electrocuted.

Fascinating as these details are, the screenplay by Dustin Lance Black lacks tension. The movie focuses tightly on Hoover and Tolson. Portraying the impact of Hoover’s FBI — say by showing the culmination of a kidnap case that successfully returned a child to his parents or by depicting a victim of Hoover’s blackmailing of members of Congress and presidents — would have livened up the narrative.

As John J. McDermott, who headed the Washington field office under Hoover and eventually became deputy associate FBI director, told me for my book “

The Secrets of the FBI,” Hoover would put members of Congress and presidents “on notice that we had something on them, and therefore they would be more disposed to meeting the bureau’s needs and keeping Hoover in power.”

The droning voiceover narration is enlivened by DiCaprio, whose depiction of Hoover is a tour de force. For each shoot, he had to undergo up to 6 hours of makeup work to age his face with prosthetics.

As for the relationship between Hoover and his deputy Tolson, Hoover and Tolson, both bachelors, were inseparable. They ate lunch together every day and dinner together almost every night. They vacationed together, staying in adjoining rooms, and they took adoring photos of each other.

Hoover lived with his mother in the family home until she died when he was 43. As noted in “The Secrets of the FBI,” he left his estate — worth nearly $3 million in today’s dollars — to Tolson.

As the movie suggests, given their emotional attachment, Hoover and Tolson had a spousal relationship as the term is broadly defined.

Ronald Kessler is chief Washington correspondent of Newsmax.com. He is a New York Times best-selling author of books on the Secret Service, FBI, and CIA. His latest, "The Secrets of the FBI," has just been published. View his previous reports and get his dispatches sent to you free via email. Go Here Now.

© 2026 Newsmax. All rights reserved.